Migori, Kenya — Sixty-four-year-old Petalis Ouma has suffered chronic cough and chest pains. Lately, the chest pain has been worsening. He has never smoked a cigarette but cultivated tobacco for years in his home in Migori, a region in southwestern Kenya where tobacco is one of the primary cash crops.

Growing tobacco has a detrimental effect on the health of the farmers who routinely touch and inhale the plant’s toxins. Between 2012 and 2018, tobacco leaf exports from African countries increased by more than 10%, with East African countries producing 90% of the tobacco farmed in Africa.

World Health Organization (WHO) in partnership with World Food Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, in collaboration with the Kenyan government, have initiated a programme to help farmers transition to producing more sustainable crops and lead healthier lives. Ouma is one of the 900 farmers making the switch.

Kenya’s Migori county is one of three where most tobacco farming in Kenya takes place. The cash crop contributes less than 1% to Kenya’s GDP while leaving those who grow it in poverty.

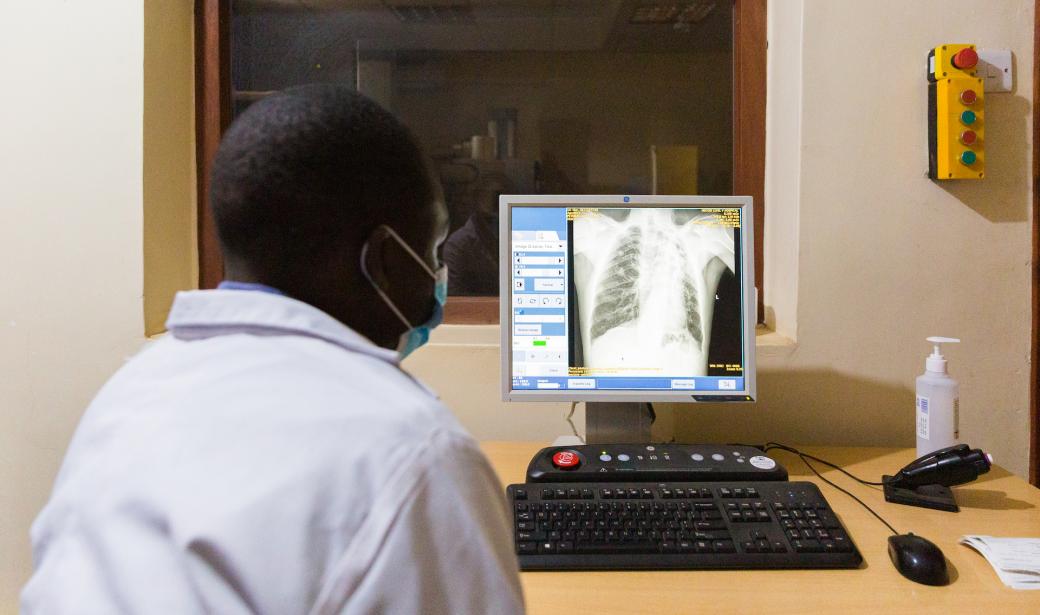

Dr Francis Manyinza isn’t surprised by Ouma’s condition. As a senior clinician at the county referral hospital, he has seen his fair share of tobacco farmers wheeze their way through the hospital’s corridors.

“The list goes on. Many tobacco farmers are also malnourished. The pesticides they work with are toxic and they usually don’t have protective gear,” says Dr Manyinza.

“We all know tobacco is bad for us. Just the smell makes me sick,” Ouma says. After a laboured breath, he continues, “This is poverty. Until recently, tobacco was our best chance to make money.”

Philip Obonyo sits with his youngest daughter and recalls the painful memory of the cancer that took his first wife. He stopped growing tobacco immediately after her passing.

“I lost my wife because of the [effects of tobacco] so why should I continue with something harmful to the life of my family?” Obonyo says, voice and hands trembling. “Family matters a lot.”

Obonyo continues, “I keep telling people it’s not worth it. Maybe there is money in tobacco but there is no profit. You will use your trees, you will use your family and you will use your labour. Once you pay for all these, the trees, your family and yourself for the work, and the farm inputs, there’s no profit left.”

Kenya was one of the first countries to ratify the legally binding WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and subsequently adopt the Kenya Tobacco Control Act. Both documents stipulate a need for an alternative to tobacco production that protects those whose livelihoods depend on growing it.

Through WFP’s local procurement initiatives, there is now a long-term market for high-iron beans in Migori.

“This market gives Migori’s tobacco farmers a new way to earn a living with none of the negative health effects that come from growing the high-labour intensive and toxic tobacco plant,” says Dr Abdourahmane Diallo, WHO Representative in Kenya. “This is a new way to fight the tobacco epidemic that has stolen so many lives.”

Obonyo also saved some beans from his last harvest that he and his family eat on Sundays after going to church. “They’re a little sweet, the children love it.”

It was through Rugar that Ouma and Adero learned of the alternative option.

This season Ouma will use the five acres where he previously grew tobacco to grow the beans. The beans can be grown and harvested two to three times a year, whereas tobacco offers only an annual yield.

“I have a lot of difficulty seeing the family like this, they all have skin problems,” she says. “And listen to me! I don’t breathe well.”

Communications & Social Mobilisation

Tel: +254 722509403

Cell: +254 710 149489

Email: mwakishaj [at] who.int (mwakishaj[at]who[dot]int)

Communications and marketing officer

Tel: + 242 06 520 65 65 (WhatsApp)

Email: boakyeagyemangc [at] who.int (boakyeagyemangc[at]who[dot]int)