Nairobi—Since the launch of the Tobacco-Free Farms initiative in 2022, over 9000 farmers in Kenya have shifted from tobacco farming to alternative livelihoods.

The initiative’s primary aim is to provide tobacco farmers with sustainable, profitable livelihoods by encouraging them to grow alternative food crops. This not only addresses the health risks of tobacco farming but also the social, economic and environmental damage it causes.

Tobacco-Free Farms is a joint global initiative of World Health Organization (WHO), ministries of health and other UN partners. In Kenya, the initiative has high-level support from the national and county governments.

At the outset of the initiative, WHO Kenya trained a cohort of 80 community health workers in western Migori county to conduct outreach among tobacco farmers on the dangers of tobacco farming and the alternatives available. In 2023, Migori county and one of its model farmers, Sprina Chacha, received the WHO Director-General's World No Tobacco Day award.

Since, 1500 community health workers have been trained and the initiative has expanded to three more counties.

“The work was overwhelming, and the worst part was having to involve my children. I didn’t want to, but without their help we couldn’t earn enough to eat,” he recalls.

“The most difficult time was during the leaf tying process,” he continues. “The tobacco companies had high demands, and the pressure was intense. In the evenings, I would hide my children so they could secretly help tie the leaves. Sometimes on Sundays, they would also help us pick them. I couldn’t afford to hire anyone, so my whole family had to pitch in.”

But the yield is paltry. In Kenya, tobacco farmers can earn less than US$ 110 a year and smallholder farmers often use their entire plot of land to grow tobacco instead of food.

“Before she knew how to walk, we used to bring her to the tobacco field and lay her under the tobacco leaves while we worked on the fields,” says Kikulesi. “My wife would be helping me on the farm and there was no one at home to look after the baby.”

"When Neema got older she used to miss 2‒3 days of school a week to help out on the farm during the picking season,” he recalls.

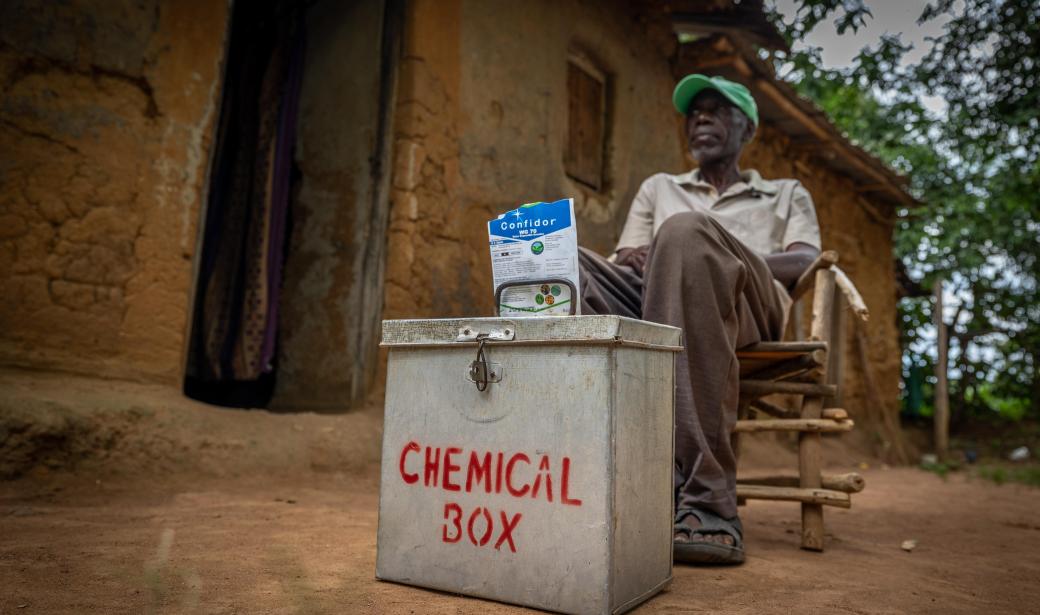

Farmers suffer from upper respiratory illnesses and symptoms consistent with Green Tobacco Sickness due to nicotine absorption through the skin when handling wet tobacco leaves, exposure to heavy use of pesticides and to tobacco dust. Children who are involved in the farming process are often stunted and malnourished.

“We had to use strong chemicals to grow tobacco ‒ pesticides and fertilizers that were expensive and harmful. They caused headaches, coughing and skin problems, especially when we didn’t have protective gear,” says Lusakia.

Farmers suffer from upper respiratory illnesses and symptoms consistent with Green Tobacco Sickness due to nicotine absorption through the skin when handling wet tobacco leaves, exposure to heavy use of pesticides and to tobacco dust. Children who are involved in the farming process are often stunted and malnourished.

“We had to use strong chemicals to grow tobacco ‒ pesticides and fertilizers that were expensive and harmful. They caused headaches, coughing and skin problems, especially when we didn’t have protective gear,” says Lusakia.

“I earn more than I ever did with tobacco, and the work is easier. I don’t have to involve my children anymore, and I can even use some of the beans to feed them,” says Lusakia.

Gerald Eroto and his wife Janet from Ataba village in Busia County, also in the West of Kenya, swapped tobacco farming for nyota beans seven years ago.

“I pay school fees using income from the beans,” says Eroto. “Sometimes, I even deliver beans directly to schools in exchange for part of the fees.”

“It has also enabled me to pay college tuition for my son, who is now studying at a university in Embu.”

“Tobacco-Free Farms has had a profound impact on farming communities,” says Dr Joyce Nato, Technical Officer for Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in WHO country office in Kenya. “It enables farmers to pay school fees, access healthcare and invest in the future of their families.”

Communication officer

WHO Kenya

Tel: +254 740 466 426

Email: printg [at] who.int (printg[at]who[dot]int)

Communications and marketing officer

Tel: + 242 06 520 65 65 (WhatsApp)

Email: boakyeagyemangc [at] who.int (boakyeagyemangc[at]who[dot]int)